Why the P-47 Thunderbolt, a World War II Beast of the Airways, Ruled the Skies

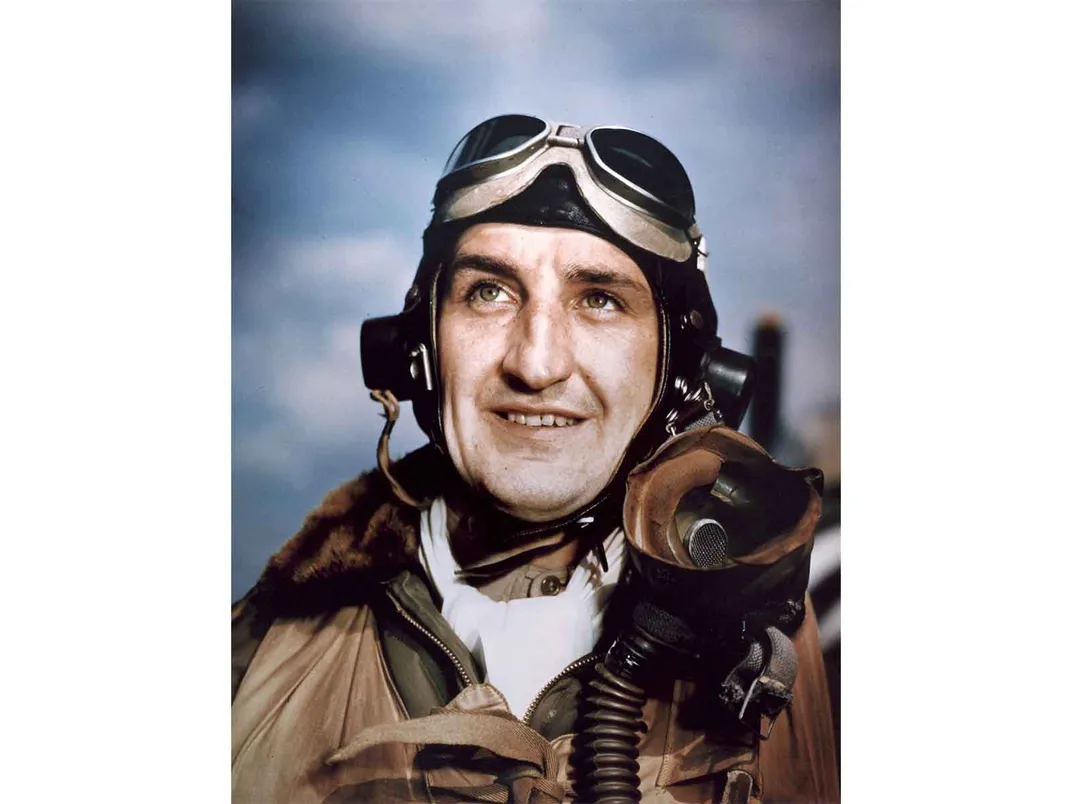

In the skies high above Germany on November 26, 1943, Major Gabby Gabreski was pushing his Republic P-47 Thunderbolt hard. The 56th Fighter Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces had been ordered to cover the withdrawal of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses after bombing the industrial city of Bremen.

Gabreski, leading the 61st Fighter Squadron, was flying fast to rescue the American bombers, which were being swarmed by Nazi fighter planes. As they arrived on the scene, the commander ordered his pilots into the fray.

Gabreski could see targets everywhere. He gunned the turbocharged engine in his powerful plane and went on the attack. Gabreski spotted a Messerschmitt Bf 110 and drew a bead. At 700 yards, he let go with a burst from his eight .50-caliber machineguns, causing the twin-engine plane to burst into flames. He had to dive to avoid colliding with the disintegrating aircraft.

Minutes later, Gabreski spotted another Bf 110. He throttled up his massive 2,000-horsepower engine and zoomed in on the unsuspecting fighter. Gabreski fired and hit the plane at the wing root. It spiraled to the ground in a massive fireball.

Those two kills nearly 80 years ago this month were his fourth and fifth of World War II. Gabreski was now an ace. He would go on to shoot down 28 enemy aircraft to become America’s top ace in Europe. All of the kills would come at the controls of the P-47, one of the most rugged fighter planes of the war.

Weighing 10,000 pounds empty, the Thunderbolt was the largest single-engine fighter built by any country during World War II. Fully loaded with pilot, fuel and armaments, it topped out at more than 17,500 pounds—yet was exceptionally fast as a fighter-bomber, achieving a top speed of 426 miles per hour. It was arguably the best ground-attack aircraft America had at that time.

“The P-47 was one of the most versatile aircraft we had in World War II,” says Jeremy Kinney, curator and chair of the aeronautics department at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, which houses a P-47 in its collections—on view at the museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. “It was not as famous as the P-51 Mustang, but it ranks as one of the best for that era. The Thunderbolt was the hammer: big and strong, it could take a lot of punishment and still deliver a lethal blow. It was unparalleled as a ground-support aircraft and it was also a great dogfighter.”

In the European Theater, P-47 pilots were responsible for destroying more than 7,000 enemy aircraft—more than half in air-to-air combat. Though at least twice as heavy as the Supermarine Spitfire, the Thunderbolt was surprisingly agile and fast. It was well-regarded for its exceptional diving ability—considered crucial by ace pilots—and how it transformed that energy into climbing power to get back into the fight.

“As an escort plane for bombers, it more than held its own against the best the Luftwaffe had despite its range limitations,” Kinney says. “With eight .50-caliber machineguns and the capability of carrying rockets and bombs, the P-47 was a formidable aircraft against ground targets.”

And rugged too. Not long after Gabreski became an ace, his engine shut down at high altitude when his turbocharger was hit by a 20 mm cannon shell from a Messerschmitt Bf 109. He was able to outmaneuver the enemy aircraft and restart the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engine at a lower elevation.

“The Thunderbolt could take a lot of damage,” Kinney says. “It was designed to be rugged and became a preeminent fighter of World War II, flying in all major theaters and developing this mythic quality because of its durability.”

The aircraft was the brainchild of Alexander Kartveli, lead designer for Seversky Aircraft Corp., predecessor of Republic Aviation. In the 1930s, he created the Seversky P-35 for the U.S. Army Air Corps, which served as the model for the P-47. The new fighter made its first flight on May 6, 1941.

“Kartveli, a Russian immigrant, was one of America’s great aviation designers,” Kinney says. “He revolutionized fighter aircraft with the semi-elliptical wing and more powerful engines equipped with turbosuperchargers.”

During World War II, the Thunderbolt flew more than half a million missions and dropped 132,000 tons of bombs. It had an exceptionally low rate of loss—.07 per mission—while Thunderbolt pilots racked up an impressive 4.6-to-1 aerial kill ratio. Of the 15,683 P-47s built between 1941 and 1945, only 3,499 were lost in combat.

The Thunderbolt on display at the Hazy Center is one of only a few dozen that survived the conflict and the march of time. Built in 1944, this P-47D-30-RA was used primarily as an aerial gunnery trainer in the United States. After the war, it became part of the U.S. Army Air Forces Museum, now the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, before being transferred to the Smithsonian. It was restored by Republic Aviation for the 20th anniversary of the fighter’s first flight in 1941.

Looking at the shiny aluminum fuselage of the P-47, it’s easy to see why World War II pilots relied so much on this aircraft. Large and lasting, she was the beast of the airways and could deliver far more punishment than she took.

In fact, that reputation for durability became the inspiration for another remarkable aircraft: the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II. Known affectionately as the “Warthog” for its unusual aesthetics, it followed in the footsteps of its namesake to become one of the most reliable and rugged close-air-support aircraft in the U.S. Air Force.

“The A-10 pays homage to the P-47 as a ground-attack aircraft,” Kinney says. “Both are durable and amazing machines that were and are crucial to our country’s defense.”

Gabreski may have been just as tough as both aircraft. He flew a total of 266 combat missions and survived both a crash landing and internment in a German POW camp. In addition to his 28 kills in World War II, Gabreski shot down six aircraft in Korea, becoming one of only seven American pilots to be an ace in two wars.

In the latter conflict, he flew jets and certainly came to appreciate their speed and nimbleness. However, the turbocharged supremacy of the P-47 Thunderbolt in World War II left a lasting impression with Gabreski, who died in 2002.

“That added power meant so much,” he said in an interview later in life. “It meant that I could do combat with the enemy over his territory at all altitudes and I could break off at will. I had more power than he had and I could corkscrew, go up to altitude and he couldn’t follow me.”

Editor’s note, January 24, 2022: This story has been edited to reflect that the Thunderbolt dropped 132,000 tons of bombs during World War II, not 132,000 pounds